About two years ago, I became borderline obsessed with the new kid on the block in usability land: UX writing. I’m talking about the discipline of crafting words and sentences that help shape the user experience, by guiding a user through a digital product with clear, concise and useful copy. UX writers design the user experience with words.

For a few months now, I’ve been working as a mentor in the UX Writing Academy program of the UX Writing Hub. They gave me the opportunity to reconnect with my passion for language and translation, by signing me up for the online conference for localization professionals LocWorldWide. I had the pleasure of listening to stories, projects and challenges of localization managers of some prominent international companies, such as Microsoft, Atlassian, Shopify, Adobe and many more.

As a young discipline, UX writing nowadays is being shaped by people with a plethora of different backgrounds. By the end of the conference however, I was convinced that localization professionals also have at least as much affinity with UX writers as other ‘more traditional’ professions that more often transition into UX writing, such as journalism, communications, psychology or design.

Let me give you four reasons why I believe that localization experts are in a great position to pick up UX writing in no time!

1. They love to play with words

UX writers often need to get creative with words. On a daily basis, they are dealing with character limits, design restrictions or other aspects of interface writing that force them to use words to come up with a clever solution.

Or sometimes, they just feel that a certain word or expression is not 100% what they’d like to say, or that it doesn’t address the mindset of the user in that particular part of the user journey. Knowing a lot of words and having a good understanding of their nuance come in handy in such cases.

Many localization experts have a background in translation, philology, journalism or another discipline that involves language. Often, they know a few different languages and try to regularly savour each and every one of them. They devour books in one language, listen to music in another language and will relax at night watching a series in a third language. They’re the type of people that will always learn a handful of words of the local language when vacationing abroad. Words for them are like magic spells that open doors in strange lands.

They have a deep understanding of both their mother tongue and one or more other languages, all of them within their cultural context. It gives them a broad-ranging set of words, expressions and thinking frameworks to clarify exactly what they want to express.

At the conference, Christian Artopé of the Berlin-based advertising agency GUB.Berlin presented a great example of how creative localization experts can be with words.

Their client, the ridesharing service Berlkönig, is well-known all over Berlin for its snarky, typical Berlin sense of humor in their advertising. To reach also non-German speakers in Berlin, they had to find a way to translate the cheeky sense of humor in their German ads to English.

One of their ads shows a Berlkönig van parked right in front of a swingers club (not the dance kind of ‘swinging’, just to be clear here). The German text used to say ‘In Berlin teilt man doch gerne’, which translates to ‘In Berlin people just love sharing’.

You get the ambiguity, right? If Berliners aren’t sharing a ride, they might as well be sharing their partner. Nevertheless, a literal translation to English doesn’t really evoke the same effect as it does in German, where the sexual meaning is clear right away.

The challenge was to come up with an expression that relates to both the ride with the van and… well, the other ride.

So this is what they came up with.

Clever, right! Another sentence that applies to both the van and the club with a different meaning, but the same naughty, tongue-in-cheek sound.

A perfect example of how a broad knowledge of words, expressions, cultural references and other language-related knowledge allow localization experts to be creative with words. Bearing in mind the UX writing rules of clear, concise, conversational and useful copy, they can do great things as UX writers!

2. They are sensitive to context

Localization experts know that language never exists on its own. It is always embedded in a geographical, historical and cultural context. There can be differences on so many contextual levels – even for native speakers of the same language, a translation that doesn’t look at the context can lead to hilarious, confusing or painful situations.

Chris Jaekl of Shopify talked about his journey in localizing an e-commerce platform for different markets. He gave a good example of why it’s crucial to take the context of the user into account, if you want to create a good user experience.

When logging in to Shopify, the user is greeted by the interface. Jaekl gave the example of a user with the name ‘Ken Tanaka’. In English, an appropriate way of greeting this person would sound like ‘Hello Ken!’. Sounds reasonable, right? For English speakers it definitely does.

When translating such a simple sentence literally to Japanese, the user would feel offended by how impolite the interface is greeting them. Japan has a culture with different levels of respect and politeness when addressing another person. This has found its way into the language, which has many different so-called honorifics. These different linguistic forms express the relationship and social hierarchy between people.

An interface addressing a user in an informal way like ‘Hello Ken!’ is just unheard of in Japan. So Shopify had to take this cultural reality into account when creating the Japanese version. Even for a simple thing as saying hello to your user.

The greeting on the Japanese version of Shopify would be 田中さん (Tanaka-san), which would literally translate to ‘Tanaka, Sir’. Jaekl even added that a more appropriate way of translating this would be something like ‘Honored customer Mr. Tanaka, Sir’. Sounds weird, right? Well, in Japan it is business as usual.

This example shows that context can make a real difference between successful and failed communication when translating content. Rather than translation, localization professionals often talk about transcreation. It refers to transferring a message from one language to another, while maintaining its intent and context and making sure that style and tone resonate with the target audience.

UX writers are designers with words, and designers also have to be sensitive to context. They ask themselves many questions before writing a single word: What information does the user already have? What are they expecting at this stage of the user journey? What could they be concerned about? Which device will they use? What are their needs, frustrations, expectations? And many other questions.

Localization experts already have this natural reflex to take the context of the user into account. To make the transition to UX writing, they just need to get familiar with the contexts needed to write interface copy. You could say that they should go on a quest to broaden their contextual horizon.

3. They care about user needs

One of the panel discussions during the conference touched upon the topic of retrofitting localization into a product and making it accessible for other markets. Melanie Heighway of Atlassian mentioned that localization experts should try to create the impression that the app was conceived and created especially for this market. That’s why you should make as few concessions as possible in terms of usability, even if this means additional work for designers and developers to make changes to the product.

Localization experts that transition into a UX writing role will understand the importance of thorough user research and how it can improve the output. Thanks to their role as a gatekeeper to an entire group of users that speak a different language or come from a different background, they want the best possible experience for each user.

Rahel Anne Bailee talk focused on localization in the healthcare sector. In this context, localization professionals may have to deal with some very personal and private information. Depending on specific cultural sensitivities, translation can get tricky. She made an explicit comparison to UX professionals, who have to deliver high-quality work while juggling empathy, context-sensitivity and personalisation.

She gave some interesting examples of gender-sensitive issues. In India, for example, a third gender is officially recognised. In other cultures, references to alcohol or medication can be highly problematic. In other cultures, medical aspects such as birth control, or palliative care may be taboo topics.

Localization professionals should be aware of these aspects and understand their sensitive nature, to to avoid shocking or offending their target audience.

So it’s safe to say that localization professionals, just like UX writers, are real advocates for the user.

4. They want to be included early on in the process

This is a pet peeve for many UX writers. Often, designs of a digital product are ready and approved. Right before moving forward to the development stage, the ‘word person’ is asked to do a quick check of the words in the interface. They are told that they need to polish spelling and grammar, or replace ‘Lorem ipsum’ with something that makes sense. As many UX writers know, this is usually the start of new discussions and challenges.

Way too regularly, product teams still think about the content at the end of the design process. This way, the functionality of each piece of content is not taken into account when designing. Ideally, a product team should start by thinking about how each piece of content will guide the user through the interface and help them to reach their goals. This is a great way to avoid or reduce design issues in a later stage of the process.

Localization experts come across similar challenges and have taken on similar battles as UX writers. Due to a number of inherent differences between languages, some interfaces just can’t be populated with another language without glitches or larger issues arising.

Conventions like punctuation, use of symbols or date formats can be confusing for the user. Where in the US ‘10/08’ means 8 October, the same expression in France means 10 August. For digital products for air or train travel, users might end up buying tickets for the wrong date, if not properly localized.

Another example is the pluralization of nouns after numbers. The plural of ‘table’ in English will be ‘tables’, regardless of the number that proceeds the word. In Polish however, the plural of ‘table’ (stół) will take different forms depending on the number. There are 2, 3 and 4 ‘stoły’, but 5, 6 or higher ‘stołów’. In an interface where words need to be pluralized according to the input of the user, the developer will be happy to get this information up front.

Also, the overall length of words or sentences in a given language can make designs tricky to localize. Some languages are rather compact, others are naturally long, such as German. Adding German text to an interface that has been designed for English copy will almost certainly be problematic due to space issues.

During a panel conversation, Andy Andersen of Tinder mentioned that his efforts in evangelizing the early involvement of localization in the design process have paid off. To save their German colleagues from unnecessary headaches while translating the interface, their American designers now know that they need to leave extra space for other languages.

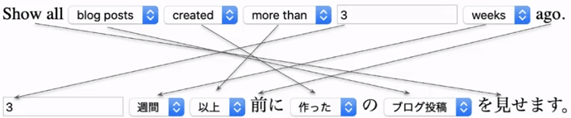

Sometimes, the syntax of a language can cause problems, at least when the design imposes a certain word order in a sentence. Chris Jaekl of Shopify shared the image below, where a certain interface has been localized from English to Japanese. You can see right away that design and development had quite the task to make sure this all worked as it should.

This is a hypothetical example to give an idea of issues that occurred during the localization of an interface to Japanese. With the help of localization experts, the developers had to rearrange all the hard-coded elements to make sense for users of the target language. As you can imagine, a painful and probably costly operation!

Or what about localizing in languages where you don’t read from left to right, such as Hebrew, Arabic, and Farsi. Software internationalization consultant Gilad Almosnino talked about this specific issue and the challenges it can cause for the UI layout.

He presented the principle of UI mirroring, where designers create the mirror image of an interface for a similar feel and flow for both a LTR (left-to-right) language interface as for the version in the RTL (right-to-left).

He also talked about the challenge of including LTR words in RTL interfaces. He gave a simple example of the Hebrew IKEA catalog, where the title includes one Swedish word. This means that the reader has to change the reading direction mid-sentence for just one word and then change again to the original direction in Hebrew.

Almosnino explained that this situation has to be embedded carefully in the code through Unicode BIDI (bi-directional) Control Characters – special pieces of code indicating that the reading direction changes at some point in the text.

Even if you include localization peeps in advance, localization of an interface that includes a change in reading direction is a challenge by default. Make sure to involve the right people here, if you don’t want your design and development colleagues to have nightmares.

Patricia Gómez Jurado of the gaming company King and Mario Ferrer of Skyscanner gave a joint talk about why localization and UX writing should collaborate closely, or even be one team. They seem to be the front runners of including both UX writers and localization experts early on in the design process.

During their talk, they discussed how they set up weekly or bi-weekly meetings where designers present their newest creations for their localization colleagues. This way, language-related design issues can be spotted early on and the designers can explore alternative ways to make their designs more localization-friendly.

They also use collaboration tools such as Lokalise and Figma to keep everyone in the loop about design updates. This allows localization experts to spot and report potential bottlenecks at all times in the process.

Localization professionals obviously have many other qualities. But the ones I mention here already paint a good picture of why it is very likely that they would make great UX writers.

If you’re a localization pro who hasn’t discovered UX yet, I’d definitely recommend looking into it! And who knows, you might get hit by the same UX writing spark that hit me a couple of years ago!

Next steps

Sounds interesting? Start by signing up for UX Writing Hub’s newsletter and check out the free foundation course.

Thank you Anja Wedberg for your input on this article 🙏